Extracts from 'Shanghai Future: Modernity Remade' by Anna Greenspan

A book published in 2014, about Shanghai's emergence as the hyper-modern city of the future, with a spirit of futurism that has been long dead in the West.

Urban Planning — A Metaphor for Futurism.

Contemporary Shanghai is best viewed from those zones of the city that are still incomplete. Downtown, in People’s Square, Shanghai’s Urban Planning Museum showcases a miniature model of the city that corresponds to a future date. Structures that are already standing are modelled in white, while those that are as yet unfinished are left transparent. Residents are said to come here before buying property to check if their houses will soon be torn down. In the model, the giant towers that are to come dwarf even the city’s brand new skyscrapers.

… Everywhere there is the sense that the city is more process than place.

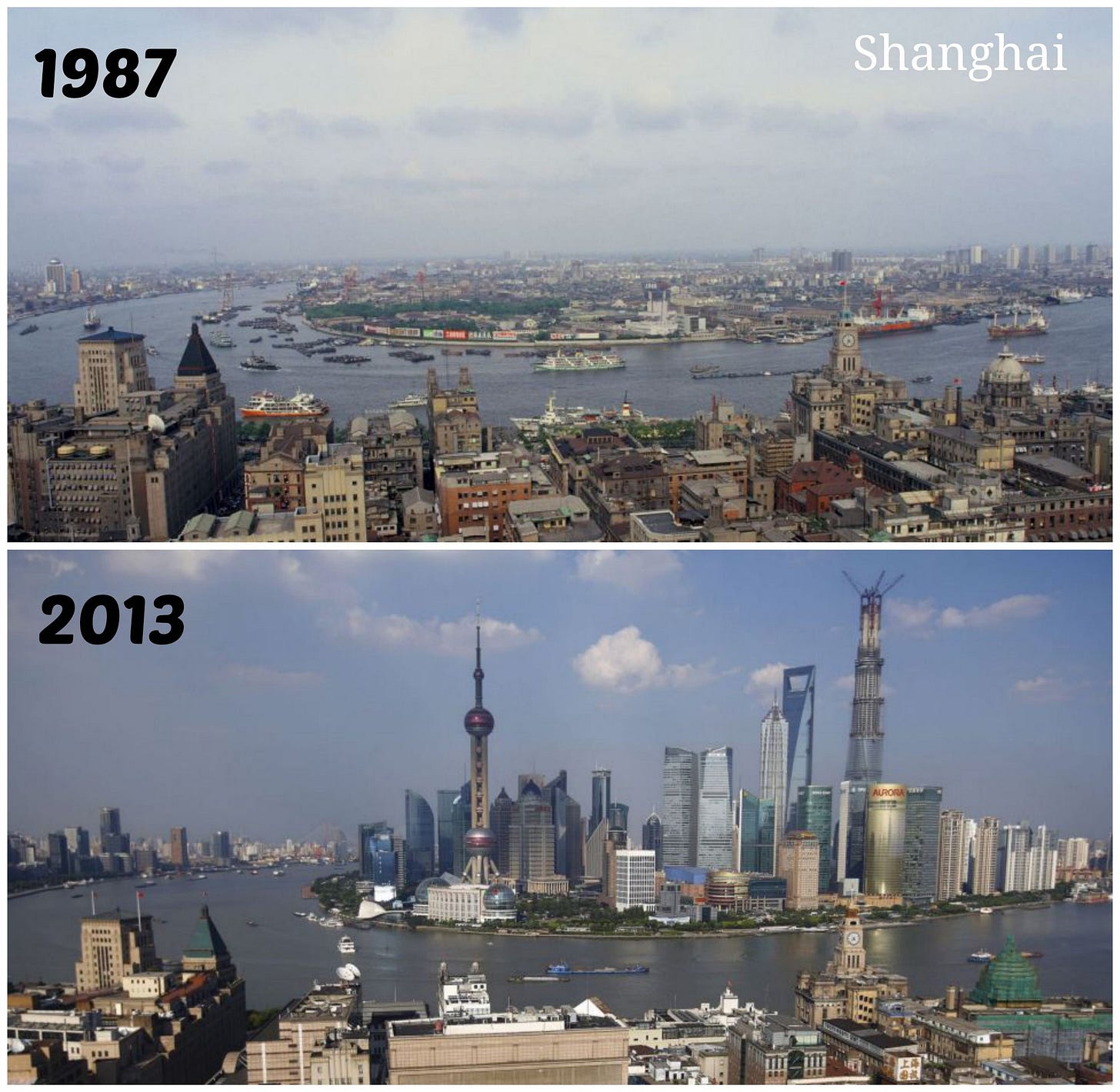

To visually grasp the incredible pace of Shanghai’s (quite literal) rise, refer to these two pictures taken at the same spot, twenty six years apart. Many of you reading this are in your 20s —how much has your city grown and risen since your birth?

Look at the 1987 image. While the western shore (Puxi) is dominated by the colonial architecture, the Pudong district, on the other shore, is nothing but a nondescript flatland of factories, shanty-town housing and farmland. Zhao Qizheng, then deputy mayor charged with the development of Pudong, bemoaned the imbalance, describing 1990s Shanghai as a ‘maldeveloped cripple’. Now glance at the 2013 image. Breathtaking. But its not just about skyscrapers:

To remake Pudong as futurist fantasy required not only that basic infrastructure be developed to meet existing needs but also that the area be geared towards servicing all that was imagined would come. From the start, plans for Pudong included the creation of sixteen passenger ferries, four car ferries, a deep water port, an airport, a rail network, a metro system, an urban highway system with numerous bridges and tunnels, a modern water and sewage system, and a proper telecommunication network. In the decade between 1990 and 2001, an investment of more than 93bn yuan ($11.23 bn) was made in the infrastructure of Pudong.

Top-Down Origin?

Despite appearances to the contrary, Pudong (the western district of Shanghai) was not constructed through the top-down dictates of a centralised state. Instead, the district was designed by committee, through a hodgepodge mixture of compromise and experiment that emerged precisely at the moment Shanghai opened its door to the outside world. While it may seem as if Pudong conforms to the rigours of a plan, in fact, it, more than anywhere else in the city, was built at the cusp of China’s transition away from the planned economy. ‘Compared with the traditional way of managing area development in China—closed, top down, opaque, bureaucratic and government controlled—the development of Pudong,’ argues Yawei Chen, ‘showed an evolutionary trend, more open and interactive, governed by a hybrid form of control.’ Deng Xiaoping urged officials to view the development of Pudong as an opportunity to ‘liberate thought’ and not to be ‘straitjacketed by predetermined ideas’.

…Pudong, then, is better thought of as an economic strategy than as an urban design. It was intended as a mechanism through which the city could transition from a rigidly top-down bureaucratic system to the more flexible and open networks of the global market. Only this explains, as Chen argues, why foreign capital so eagerly invested in Pudong, risking billions of dollars, especially in the early years when the district’s development was little more than fantasy. ‘The strong hand of an authoritarian state alone,’ she writes, ‘is insufficient to explain why so many investors and multinational corporations flocked to the area’.

Building on the foundations of Le Corbusier:

At the core of Shanghai World Financial Centre’s architect, Minoru Mori’s vision of the modern city is the contradictory postulate—essential to Le Corbusier’s thought— that to decongest the city it is necessary to increase the density of the urban core. This seemingly paradoxical idea is best understood in contrast to the opposite inclination: decentralisation. Faced with the pollution, squalor and chaos of newly-industrialised cities, governments and planners tend to support a strategy of fleeing outwards, believing that spreading people out into small suburban towns or ‘garden cities’ that are built on the urban edge could deintensify the city and make mass urbanisation more manageable. Le Corbusier vilified this impulse with characteristic ferocity, attacking decentralisation as an ‘illusion’, ‘falsehood’ and deceptive ‘mirage’. Garden cities with their ‘mock nature’ should be banned, he proclaimed. Suburbs should be eliminated. Instead, Le Corbusier advocated for compact cities that cram people tightly together, rather than extending ever outward. In the Metropolis of the Machine Age, we should ‘pile the city on top of itself’.

Central to Le Corbusier’s argument is that as a consequence of this intense urban density the city can be made green. Urban dwellers have no need to escape into the false nature of suburbia, he insisted. Instead, nature could be ‘brought into the cities themselves’. The key to this dense but decongested metropolis infused with the natural world is the skyscraper. When work, leisure and housing are packed inside mega-towers, Le Corbusier maintained, plenty of room can be left for trees, flowers and open spaces. His sketches show clusters of high rises set within large areas of green. In his plans for a ‘contemporary city’ the ‘skyscraper in the park’ would replace the unruly chaos of urban sprawl. The ‘Contemporary City’, wrote Le Corbusier is a ‘Green City’ .

Rebirth of Modernity

Modernity, it is now widely maintained in the West, belongs to history and we have entered (or perhaps, by now, even surpassed) a postmodern age. ‘Many people think the modernist laboratory is now over,’ wrote Robert Hughes in 1980. ‘

It has become less an arena for significant experiment and more like a period room in a museum, a historical space that we can enter, look at, but no longer be a part of … We are at the end of the modern era.’

In twenty-first century Shanghai, however, this temporality of anticipation, the sense of an immanent future, has returned. Today in China’s largest, richest, fastest growing metropolis a second, regenerated modernity— modernity 2.0—is currently underway

As it looks forward, Shanghai is forever harking back. Its current rise is based on a deep nostalgic memory of an ‘urban golden age’ that peaked in the 1920s and 1930s. To use Ackbar Abbas’ formulation, Shanghai today is ‘not Back to the Future, but Forward to the Past.’

… In its current embrace of the modern, however, Shanghai does more than recall its own particular history. It has also, more crucially, revived the much wider modern project of building a future city. With its super-tall towers, elevated highways and suburban ‘garden towns’, Shanghai today, increasingly resembles yesterday’s dreams of the metropolis of tomorrow.

Two seemingly contradictory forces combine to produce the future city. On the one hand there is the authoritarian will, governed by a controlling desire, that sets out to master the revolutionary transformations taking place on the ground; to envision what is to come, and to shape and plan its course. Inevitably, this is disrupted by a countercurrent that is produced by the spontaneous innovations that emerge, unexpectedly, from the everyday culture of the street. This fundamental tension, between the desire to plan for the future and the knowledge that the future is, by its very nature, impossible to foresee or control, is at the very heart of the modern metropolis

‘Every great burst of human creativity in history,’ Hall writes, ‘is an urban phenomenon’ …. Florence in the fourteenth, Victorian London, Paris at the end of the nineteenth and New York in the mid-twentieth century among many others, shows that it is these urban ‘golden ages’ that revolutionize the course of history. In these singular instants, Hall contends, a city becomes not so much a place but an epoch, that is at once both fully global and, simultaneously, hyper-local. Cities at the height of their golden age, writes Hall embrace ‘everyone who enters with a power that cannot be resisted’. ‘To become a Berliner—that came quickly, if one only breathed in the air of Berlin with a deep breath,’ Hall writes quoting a resident of Weimar Berlin, ‘Berlin tasted of the future.’

Reading Hall in contemporary Shanghai one cannot help but wonder, might we, here, too be on the cusp of such a golden age?

Time as spiraling downstream temporal flow

Westerners tend to think of the passage of time ‘as an upward line of growth and accumulation’. This conception of a rising temporal order is represented most iconically, as Land notes, in the popular image of Darwinian evolution, which is ‘characterized as a process of ascent that shows an ape creature erecting itself in stages to a climactic state of proud human verticality’.

In China, on the other hand, the course of time is depicted as a descent. Unlike English, Mandarin uses time words, rather than grammatical components as temporal markers. The two most basic of these are shang (up) and xia (down), which stand for the past and future respectively. This mode of measuring time as a ‘descent into the future’ is based undoubtedly on the water clock, a technology that dates as far back as 4,000 BC in China. The lasting impact of this ancient technology enables the Chinese, as is evident in their language, to think of ‘time tangibly as a continuous fluid,’ which flows forever downward.

Through this insistent future nostalgia, the culture of the contemporary metropolis coils time in on itself, breaking free from both the linear model of Western modernity as well as the looped cyclic stagnation of traditional Chinese time. ‘Neomodernity is at once more modernity, and modernity again. By synthesizing (accelerating) progressive change with cyclic recurrence, it produces a distinctive schema or figure: the time spiral.’